-

Classic Rock: looking for inspiration

As I complete my essay on Bob Dylan, I must now look ahead to what my social media presence should look like.

This is something that I’ve admittedly tried to write off as long as I could, for I’m personally not a fan. However, I do of course recognise that I’m unlikely to gain much of an audience without it.

In order to gain inspiration, I’ve chosen to approach the Twitter account that belongs to the YouTube personality Polyphonic. I’ve observed the ways in which he utilises his account to accompany his videos.

Based on the fact that his Twitter account bears the same name as his YouTube title, it’s clear to me that the main intention behind his presence there is to promote his channel. He also uses it to share his music-related opinions, and sees it as a platform for him to engage with his fans:

This way, he seems to have generated a decent following and sizeable engagement, based on the 25 responses he received above. By taking note of this, I’m getting closer to tapping into my most powerful tool (Moore, C. 2023).

Given the similarities found between his content and what I’m aspiring to create, Polyphonic also faces a diversity issue. His niche is one that doesn’t speak to everyone. He problematises this by voicing his support for minority groups through not only Twitter, but through his videos as well.

A Brief History of Transgender People in Popular Music – YouTube https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=OV7L8f73spA

Although I know I will have trouble engaging with Twitter regardless, I now have gained a sense of what I would like to include in this element. My perspective has broadened.

Reference

Moore, C. (2023) ‘Platform Proliferation – Perspective, Problematising, Approach and Conceptualising’, Lecture YouTube, BCM 241, UOW https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lIp80EbPVww -

Classic Rock: so it begins

Link to audio: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pE2T0jWe7VMF4s67BYPeEtqUB1-fDdVd/view

So, now that the concept of my DA is settled, I must now reflect on my layout going forward.

One of my main goals I aimed to achieve going into this revolved around perspective. I wished to place as much focus on the female artists as the male artists of the mid-to-late 60s period. Now looking at my plan, I’m not so sure if I will manage this. Many of the iconic and innovative female rock artists would not reach the zeitgeist until the 1970s, with examples including Patti Smith and Stevie Nicks of Fleetwood Mac. So while there won’t be many females serving as the topic of discussion, I hope to subvert this by bringing up the artists who emerged after this period as a direct result of the male artists I’ll be discussing (such as the ones listed above). This way, I’ll still be acknowledging artists outside of the white male variety, thus widening the perspective in my research (Moore, C. 2023).

Due to my slight lack of confidence in the video format, I’ve decided to stick to my original plan – which was to approach my project as a series of informal essays. I believe this format will create a balance between me completing a task within my comfort zone while also generating outside interest.

taken from https://community.thriveglobal.com/how-essay-writing-impacts-your-brain/

As I begin work on my first essay, I have to make sure that I’m sticking to my core concept, which is to focus on the influence generated by the artist I’m discussing. By maintaining this focus through each essay, I will be able to tell a cohesive story of the birth of art rock. In other words, this is an attempt to make my project stand out amongst the multiple YouTubers and writers who have preceded me.

References

Moore, C. (2023) ‘Content Generation – Perspective, Problematising, Approaching and Conceptualising’, Lecture YouTube, BCM241, UOW, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HHcUFQmd6rM&t=1s> -

The benefits of critiquing

Link to audio: https://drive.google.com/file/d/16XxKf2A8eLawtwYe4RvF9wpDXQemlIcZ/view?usp=share_link

In the wake of our completed pitches, now is the time for us to give feedback on the work of others. This is a task that I often dread, as I’m not a very picky person in general and I rarely feel comfortable critiquing other people, but I feel that doing this has managed to benefit me this time around. After reviewing Mali’s pitch, I’m now able to reflect on what I’m missing in mine.

Link to Mali’s pitch: https://mali648762011.wordpress.com/2023/08/11/dogs-day-in-the-life-the-pitch/

As you can see, I had trouble finding much to critique. Mali’s project revolves around her making content with her dog, which means the strength of her social media presence will heavily dictate how her project will be received in the end. Mali’s pitch has reminded me to not treat my presence on Twitter as a mere afterthought, for I will only gain traction by “mediatising” myself (Moore, Barbour & Lee, 2017).

Also, her timeline was pretty succinct… I should probably get on to that myself.

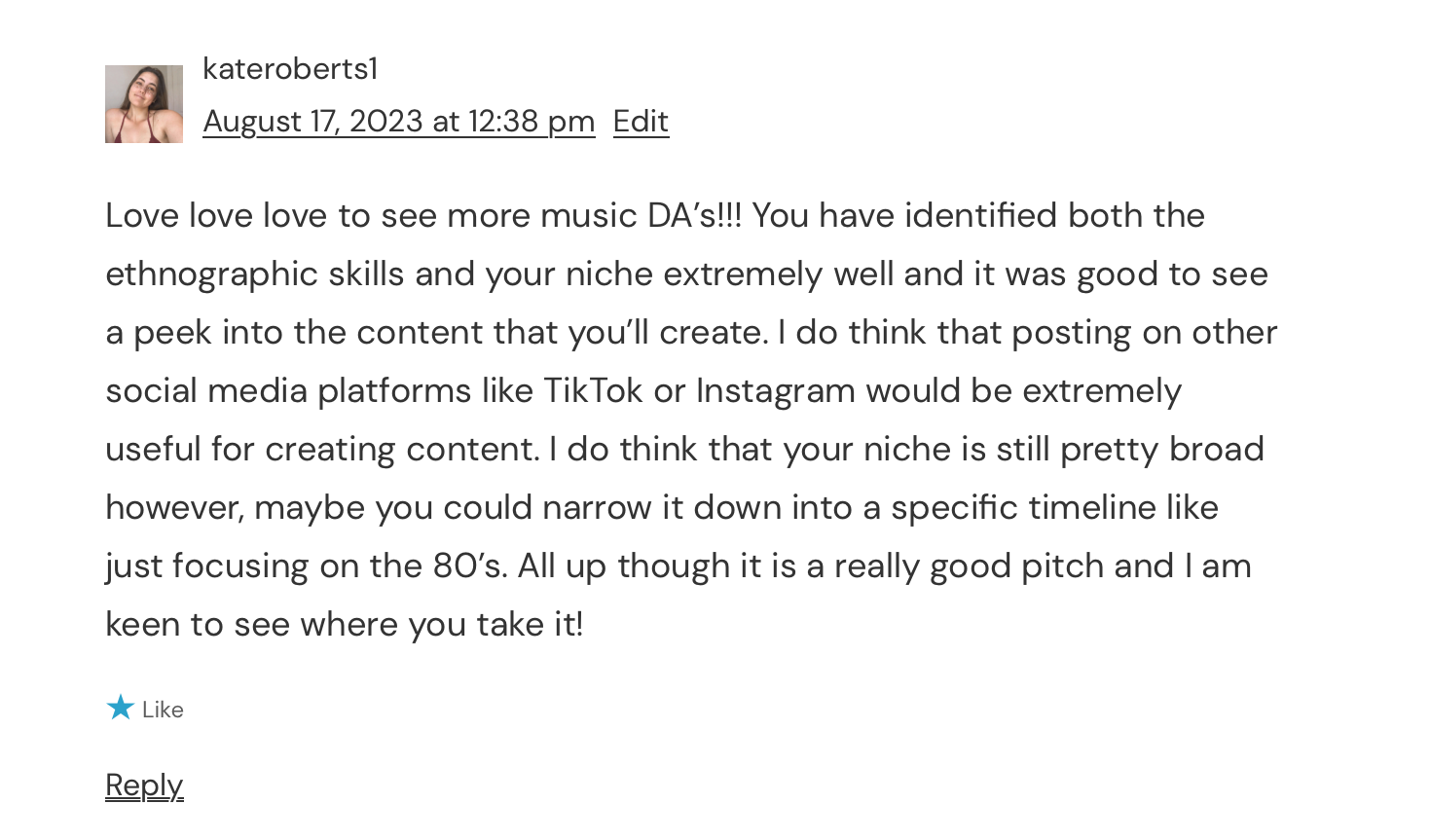

Then, of course, there’s the feedback I received.

Although Kate appears to be rather enthusiastic about my pitch, she did confirm what I had learned from observing Mali’s pitch, which is to ensure that my social media presence will be up to snuff. Kate also suggested that I should narrow my niche down further, which would probably be a good idea. Something I keep forgetting is that classic rock is a genre that technically covers nearly forty years of music (1960s-1990s) – while I’m over here insisting that it stopped during the 70s.

Even then, two decades is a lot. For this reason, I now plan on focusing primarily on the mid-to-late 60s – an era that was kicked off by the ‘British invasion’ (The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, etc) and was maintained by the ‘Album era’ (Bob Dylan, The Who, and The Beatles again).

The Rolling Stones, 1963 – taken from https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/the-british-invasion-from-the-beatles-to-the-stones-the-sixties-belonged-to-britain-244870/

Despite how much I dread it everytime, it is clearly rather useful to get feedback, and giving it was evenly useful. I’ve now narrowed down my goal, which gives me greater opportunities to dive deeper into each topic. In other words, I’ve made adjustments I may not have otherwise, and I got to see a bunch of pictures of Mali’s dog.

Reference

Moore, C, Barbour, K, Lee, K. (2017) Five Dimensions of Online Persona, Persona Studies 2017, vol. 3, no. 1

Also, here’s Kate’s pitch: https://krobertsmedia.wordpress.com/2023/08/11/aussie-punk-say-no-more/

-

The importance of Classic Rock

As I have previously discussed, the niche I’m focusing on is classic rock, and instead of going on about why I love it, I’ll be using this time as an opportunity for me to learn more about it, while also providing a platform for others to learn about it too.

As stated in the pitch, each post I make here will focus on a release of significance and the influence it spawned. An example of that would be the release of The Velvet Underground’s debut album: 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico, which garnered controversy due to its unconventional performances and unusually personal lyrics. The band’s significance to the 1960s counterculture movement is explored at length in Matthew Bannister’s article – “I’m Set Free…”: The Velvet Underground, 1960s Counterculture, and Michel Foucault (1, 2010).

The Velvet Underground & Nico – 1967 (taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Velvet_Underground_%26_Nico)

One of my main points of focus for my DA will be on exploring this era as best I can while still maintaining my ability to narrow in on my purpose, which is to explain the most important moments. This way, I won’t get bogged down by my need to just go on about the albums I love (although that still will very much be part of it).

Another ethnographic skill I plan on keeping in mind is flexibility. I could very much see my vision for this project altering slightly as I go along. I very much want to maintain a balance between generating interesting information while also still having fun with it.

Pitch:

Reference

1, Bannister, M. (2010) “I’m Set Free…”: The Velvet Underground, 1960s Counterculture, and Michel Foucault, Popular Music and Society, Vol 33, Issue 2, Pg. 163-178

-

Classic Rock: mapping it out

Link to audio: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NCkN-GUfWG91hywxfwOh0cZL9mbjx1F4/view?usp=share_link

The field in which I am researching promises a wide variety of sources. The formative years of rock (1960s-1970s) remain a goldmine for discussion, analysing and debate. Much of the inspiration I’ve received so far stems from YouTube. Within the visual essay space inhabits a wide variety of channels which dedicate themselves to music, with Anthony Fantano probably serving as the most significant figure in this space.

Another channel I find myself frequenting is Polyphonic, which is run by a person who dedicates a large portion of his content to the classic rock era, with artists such as Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd serving as common topics of discussion. What he often does is he takes certain songs or albums and breaks them down. He explains what made them a big deal; a feature that has strongly influenced the core of my project.

And of course, there’s also an endless list of essays and books written decades down the line by actual historians, which will certainly find a place in my work. Robert Christgau’s article titled Is it Still Good to Ya? Fifty Years of Rock Criticism 1967-2002 (1, 2018) is a good example of the type of sources I have at my disposal. However, I’d still rather my persona be shaped by the more down-to-earth personalities I find online, as they were the ones who pointed me in this direction to begin with.

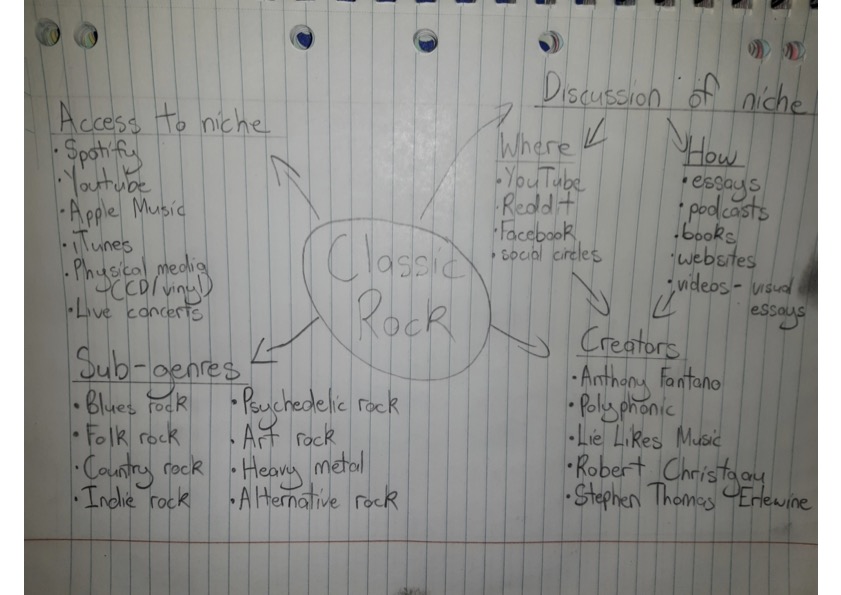

Here’s the map in all its blurrier-than-anticipated glory:

One thing I made sure to include here was a list of sub-genres that were essentially created during the 1960s-70s era of rock music – along with a few that came along later. I’m choosing to call attention to this due to the fact that classic rock in itself is less of a genre of music and more of an umbrella in which multiple genres have since become situated underneath.

Janis Joplin, taken from https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/joplin-janis-lyn

An issue I can easily imagine coming up down the line concerns a lack of diversity. The artists I listen to just so happen to be mostly white males (I promise it’s not on purpose). For this reason, I will try my best to include discussions on the innovations that were made by the female artists of that time, such as Janis Joplin and the band Fleetwood Mac (as led by Stevie Nicks). A large part of the reason why I went this route was to encourage myself to discover more artists and gain a more well-rounded understanding of this time period, and diversifying my taste will take me further towards this goal.

Fleetwood Mac, taken from https://www.timeout.com/music/15-amazing-pictures-of-fleetwood-mac-from-1969-to-now

There’s obviously still some development left to do, but there’s still plenty of time.

Reference

(1) Christgau, R. (2018) Is it Still Good to Ya? Fifty Years of Rock Criticism 1967-2002, NC: Duke University Press -

The timelessness of Classic Rock

Link to audio: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1sNOcE-DdAoRj-nC1S2TBblSlYkWmcQjY/view?usp=share_link

Upon being asked what my media niche is, my brain underwent its usual moment of panic. I began to question if I have any interest worth sharing and, more importantly, how exactly would I be able to share it?

Unfortunately, I haven’t progressed much further on the latter concern. However, I have settled on a niche: music. More specifically, classic rock.

In recent years, I have turned my interest to the albums that continue to shape how music is produced today. I’ve been captivated by the artists who were deemed revolutionary in their time, such as The Beatles and Bob Dylan, and others who were recognised later such as The Velvet Underground. In spite of passing time, their work remains significant not only due to the timelessness of their music, but also because of the ingenuity behind much of it.

Bob Dylan, 1965 – taken from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bob-Dylan-American-musician

Mickey Vallee writes that this era of music ushered in musicians who began to see themselves as “artistic visionaries” due to the freedom granted to them in the wake of the album era. They were able to “breach the boundaries of the pop mentality regime” (1, 2014), thus paving the way for the artists and genres of our current time.

The Beatles, 1969 – taken from https://www.flickr.com/photos/57440551@N03/52525023019

I’ve been able to engage in this niche largely through use of Spotify. The existence of streaming allows us to go down any rabbit hole we choose. Every day, I discover something new (despite not always being necessarily new). I’ve found that my taste has only continued to expand through my interactions with Spotify.

The influence of the 60s and 70s music scene has been explored at length through books, essays and documentaries. In recent years, we’ve also seen this exploration creeping into the podcast format. By continuing to open up discussions on this topic, we are given the opportunity to better understand that period in history and how we’ve come this far.

Although I’ve yet to settle on what kind of content or research this niche could produce, I’ve expressed an interest in not only exploring the impacts, but also the ways in which we continue to engage with the music associated with this time period.

Reference

(1) Vallee, M. (2014) ‘‘More than a feeling’: Classic Rock Fantasies and the Musical Imagination of Neoliberalism’, Culture, Theory and Critique, Vol 56, pg 245-262 -

BCM 212: Reflection

Well, that wasn’t as stress-inducing as I thought it would be.

Although it took me a little while to come up with a topic to focus on, I feel that I’ve submitted a research project that applied to me, which is rare when it comes to my assignments.

I felt adequately supported by both the weekly green books and my tutor (Rae). Once I felt confident about my chosen topic, the project felt breezy from there – and that is thanks in large part to the endless source of expert advice and guidance gifted to me and the rest of BCM.

It is because of Rae and the rest of the team that I’ve now come out of BCM 212 with a significant increase of understanding in the collecting of testimony and the ethics behind it. I’ve also come out of it with an increased understanding of how my fellow students operate when it comes their study process. My project has allowed me to become more in-tune with the others compared to before.

Of course, there’s still room for me to grow. For example, if I were to do this again, I would maybe search for a more challenging topic. I would probably also make a better effort to promote my online survey (on a side note, Rae was a great help on that front). I would probably also aim to find a more definitive answer, as opposed to communicating an open-ended discussion. Although I do believe there is value in that, it did lead to me talking in circles a little during my opinion piece. There weren’t many surprises.

I should probably also start thinking about taking project planning more seriously just in general. I knew as I was writing out the grid for Assessment 2 that I was never going to adhere to it – I never do.

However, that’s not to say I never will…? (yes it does).

And as for the option to use AI… I’m just going to pretend it doesn’t exist for now.

All in all, this was a highly positive experience. The environment created was one I found extremely inviting. Many of the things I learned here will most definitely be carried over for the remainder of my BCM classes.

Thank you

-

BCM 212: How music affects the study process

Listening to music is an activity that I see being practised on a daily basis. The reasons behind it vary; whether it be to wind down, alter the mood, or even fill a void.

I wished to discuss this with my fellow university students by relating it to something that we all have to deal with: studying. I myself have had a mixed relationship with listening to music during study sessions, with its effectiveness mainly revolving around the genre of music I choose, and sometimes my mood. I chose to look into this topic to get a sense of how others experience this. It was a chance for me, and potentially those who read this, to find commonalities within our cohort. More than anything, this was intended to be a discussion, rather than a mine for definitive answers.

I began this process by searching for outside opinions, all of which remained well under the university umbrella. As much of this project revolves around personal preference, I sought after an opinion piece. I found it in the form of a newspaper article written by Debbie Allen, a student from Northern Illinois University. In it, Allen casts a light on the vastly different effects that music can have on each individual person. Allen argues that she herself can only work in silence – “I’ve tried listening to music while studying and it’s way too distracting” (1, 2022). She justifies it here: “I’ll sing along to the song I chose to listen to or dance discreetly in my seat”. Despite this, she highlights that “not everyone feels the same way”, before bringing in testimony from others, who offer different views. Allen’s article not only gave me useful testimony, but also its nature greatly inspired my approach to the next major step in my project.

But before I moved on, I wished to find a more thorough collection of testimony. I found it in the form of another newspaper article, this time originating from the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA). Here, the writer takes personality into account, as well as “the task being performed” (2, 2015). Shannon Layman, a psychology professor, is quoted stating that “extroverts tend to do much better when they have a more energetic environment including music”, whereas the test scores for introverts are “significantly worse when they have the presence of music”. For psychology student Lana Hindi, music “causes anxiety”, with only classical music having the ability to lessen her stress.

Despite these two sources being secondary, their relevance remains in the fact that it is all testimony; a series of answers that add to my discussion. In addition to that, the points brought up in both sources serve as a precursor for the focus of my online survey.

My next step was to begin collecting direct testimony from UOW students – the centre of my project. I chose to do this in the form of a survey, as I felt this would invite a casual atmosphere and would lessen the risk of entering territory that would be considered too personal. Despite it being titled ‘How music affects the study process’, I crafted my survey in a way that would also apply to those who prefer to work in silence. I did this in order to produce answers with as much variety as possible. I also asked questions concerning the nature of their study space and preference of genre – drawing heavily from the answers found in the newspaper articles sourced previously.

The eleven responses I received featured answers that in many ways differed from the ones I had found elsewhere. At least six of them argued that listening to music helps them focus and drowns out distraction, as opposed to causing it, with one individual claiming that it “makes studying more likeable”. Many of these answers stand in stark contrast with Lana Hindi’s testimony (2). Bringing these differences to light was one of my main objectives going in, thus making this one of my most important findings. Despite this, many of them claimed that they still remain very selective when choosing what music to listen to, with one person usually finding themselves “avoiding music that features lyrics”. This feeling is reflected in the handful who chose ‘classical’ and ‘ambient’ as their genres of choice. Although Pop did take 60% of the vote, there was still a sizable percentage left over who preferred to listen to instrumental pieces while studying as opposed to songs with words. What this tells me is that many of us digest sound differently. If I were to try to search for a definitive answer on whether or not listening to music serves as a hindrance to study, it’s clear that I would have trouble finding it. When asked if they believe that music serves as an escape from what they’re working on, results were mixed. Some argued that it made their work “more bearable”, while others dismissed it as a distraction – once again reflecting how differently each of our brains work.

In the end, the subject of my curiosity became a reflection of not only what differentiates us as people, but also what makes us similar. Regardless of how vague my goals were, and in spite of the limited responses I received, what I have here is an overview of how the BCM students of UOW operate, with my secondary sources broadening this out to other Western universities and allowing my findings to feel more well-rounded.

Despite resulting in no definitive answer, I feel that I’m now more in-tune with the rest of my fellow BCM students than I was before. I hope that will be the case for others who read this as well.

Bibliography

(1) Allen, D. (2022) Unpopular opinion: Listening to music while studying is too distracting, The Northern Star, Northern Illinois University, viewed 6 May 2023

(2) University Wire. (2015) Students discuss effects of listening to music while studying, The Shorthorn, University of Texas, viewed 28 May 2023 -

BCM 222 Final Project Pitch

-

Orientalism in Aladdin

For centuries, orientalism served as a primary source for the communication of Eastern culture – by portraying it through the eyes of the Western world. Its practice began in the wake of colonial expansion in the 19th century.

In recent years, however, this practice has sparked debate for its tendency to promote stereotypes and generalisations – for being inauthentic to the culture being portrayed. Writer Rémi Labrusse claims that “the Orientalist system established itself in the broader context of a modern condition which was (and still is) felt and conceived as a general state of crisis” (1 2022, Manazir Journal). The presence of orientalism in film has been targeted; particularly films under the Walt Disney label. The two versions of Aladdin – the 1992 animated original and the 2019 live-action remake – stand among the long list of unfortunate examples in the eyes of scholars.

The original release, in its depiction of Arabian culture, was described by writers Bullock and Zhou as a “throwback to an earlier era of Hollywood stereotypes of Muslims and Arabs as inferior, quaint, exotic, backward and barbaric Oriental subjects” (2 2017, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies).

While one can argue that these faults can be overlooked as a product of their time, the argument becomes trickier in the case of the live-action remake which, despite being developed and released in a more progressive era (2019), maintains many of the original’s oriental aspects

For those unaffiliated – the beloved story takes place in the fictional Arabian town of Agrabah and tells the story of a lovable street urchin named Aladdin who comes across an oil lamp containing a magical genie. They quickly become friends, as the genie assists Aladdin in wooing the woman of his dreams – the Sultan’s daughter, who is expected to marry a Prince.

A lot of familiar Disney tropes can be drawn from this description, as well as the classic Hollywood stereotypes of Arabs mentioned previously.

In her response to the 2019 Aladdin, USC Professor Evelyn Alsutany points to older films such as The Sheik (1921) and Arabian Nights (1942) and notes their portrayal of the Middle East as “a monolithic fantasy land – a magical desert filled with genies, flying carpets and rich men living in opulent palaces with their haram girls” (3 2019, USC Dornsife). It is clear that Disney applied these tropes to their film.

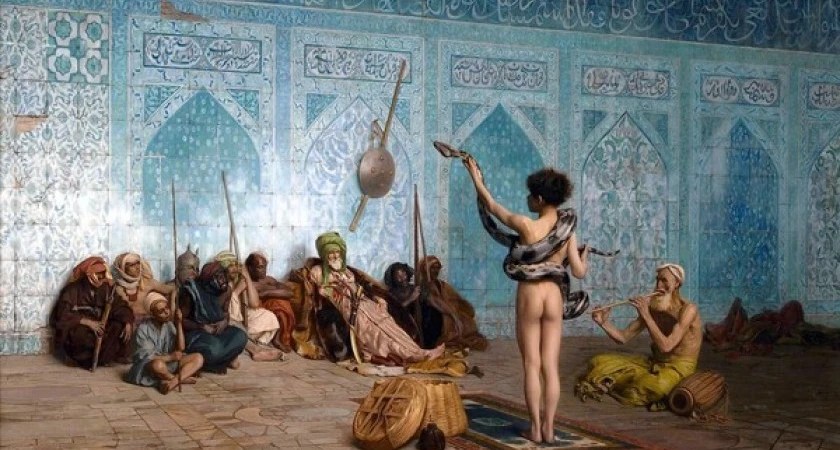

The Snake Charmer by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1879)

The depiction of Agrabah’s cultural scene brings The Snake Charmer to mind – a notable Orientalist oil painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme. The French artist’s representation of Middle-Eastern civilisation ignited debate after it became the face of Edward Said’s 1978 attack on orientalism. Said believed that this image helped perpetuate views of Middle Eastern people as “subservient”. Resemblance of this painting can easily be found in the original Aladdin, for the titular character brushes past multiple one-man shows, including a man who breathes fire, as well as a sword swallower. These are instances of what Labrusse refers to as “Hollywood Arabia” (1). The culture is presented as “barbaric”; a word also used to describe their way of living in the film’s opening song titled Arabian Night.

Another aspect of orientalism can be found in the character design choices. Outside of both Aladdin and Princess Jasmine (who each resemble your typical fresh-faced Disney leads), the screen is dominated by hooked noses, thick beards, and even thicker Middle Eastern accents. The skin tones are also noticeably darker than that of the two leads – who also happen to share American accents. Bullock and Zhou point out that “it is peripheral characters whose job it is to populate ‘Agrabah’ with Arab or Muslim-ish people” (2). They point to the apple seller in particular, who at one point threatens to cut off the Princess’ hand.

Wikipedia – Aladdin Disney Characters

The city is portrayed as backward. Aladdin and Jasmine – the two Westernised leads – spend the entirety of the film attempting to rebel against the nature of their culture – which is portrayed as overly traditional and violent. By telling a story from the perspective of a ‘street rat’, the film paints a dark picture of Arabian life, regardless of intention. Bullock and Zhou argue that Aladdin’s journey greatly resembles that of the ‘American dream’ – “like typically young and enterprising American upstarts or entrepreneurs, he used his ingenuity (along with a lot of luck) to escape such a label and to attain true love and happiness” (2) – thus painting a clear picture of a Westernised tale of the East. Jasmine’s need for independence plays similarly into American values – in this case, their vision of feminism.

By playing into tired stereotypes and telling a highly Westernised tale, it can be argued that Walt Disney Pictures – despite crafting an instant classic in the eyes of many – failed to produce an authentic portrayal of Saudi Arabia through Aladdin.

And it would appear that in spite of their efforts, the company would go on to repeat similar mistakes through their 2019 live-action remake, as it maintains much of the orientalism on display in the animated version.

Although there are some alterations, the main concept remains intact. The film, led by famed English director Guy Ritchie, once again portrays Jasmine’s struggle through a Western lens. The casting of Naomi Scott – a light-skinned, British Indian actress – as Princess Jasmine drew criticism not entirely dissimilar from the response to the design of her animated predecessor.

Naomi Scott as Jasmine (2019)

The choice to not to cast an actress of Middle Eastern descent also raised questions over the authenticity of the project, for another common criticism associated with the 1992 animated release concerns the depiction of Arabian culture as being interchangeable with other Eastern cultures. The casting of Scott sparked fear over this aspect being carried over. These fears would go on to be realised, as Alsultany observes “belly dancing and Bollywood dancing, turbans and keffiyehs”, along with Iranian and Arab accents which “all appear in the film interchangeably” (3).

Despite the removal of the more blatant stereotypes, Ritchie still manages to repeat many of the oriental aspects of the original – including the presence of American accents. Although these two films can easily be written off as ‘entertainment’ and nothing more, many still yearn for a nuanced portrayal of the Middle East – one free of Western influence – and it would appear that there are still ways to go yet.

Bibliography

(2) Bullock, K & Zhou, S. (2017) Entertainment or blackface? Decoding Orientalism in a post-9/11 era: Audience views on Aladdin, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, Vol. 39

(1) Labrusse, R. (2022) Deconstructing Orientalism, Manazir Journal, Vol.3

Aladdin, Rotten Tomatoes, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/disneys_aladdin

(3) Alsultany, E. (28 May, 2019) How the new Aladdin stacks up against a century of Hollywood stereotyping, USC Dornsife, https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/3020/aladdin-movie-and-hollywood-stereotyping/

Guy Ritchie, IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0005363/

Hibri, C. (13 Feb, 2023) Orientalism: Edward Said’s groundbreaking book explained, The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/orientalism-edward-saids-groundbreaking-book-explained-197429

Razzouk, D. (13 Sep, 2022) Why Are Kids Movies Obsessed with Orientalism? https://kazamind.com/kids-movies-and-orientalism/

Shatz, A. (20 May, 2019) ‘Orientalism,’ Then and Now https://www.nybooks.com/online/2019/05/20/orientalism-then-and-now/

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.