For centuries, orientalism served as a primary source for the communication of Eastern culture – by portraying it through the eyes of the Western world. Its practice began in the wake of colonial expansion in the 19th century.

In recent years, however, this practice has sparked debate for its tendency to promote stereotypes and generalisations – for being inauthentic to the culture being portrayed. Writer Rémi Labrusse claims that “the Orientalist system established itself in the broader context of a modern condition which was (and still is) felt and conceived as a general state of crisis” (1 2022, Manazir Journal). The presence of orientalism in film has been targeted; particularly films under the Walt Disney label. The two versions of Aladdin – the 1992 animated original and the 2019 live-action remake – stand among the long list of unfortunate examples in the eyes of scholars.

The original release, in its depiction of Arabian culture, was described by writers Bullock and Zhou as a “throwback to an earlier era of Hollywood stereotypes of Muslims and Arabs as inferior, quaint, exotic, backward and barbaric Oriental subjects” (2 2017, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies).

While one can argue that these faults can be overlooked as a product of their time, the argument becomes trickier in the case of the live-action remake which, despite being developed and released in a more progressive era (2019), maintains many of the original’s oriental aspects

For those unaffiliated – the beloved story takes place in the fictional Arabian town of Agrabah and tells the story of a lovable street urchin named Aladdin who comes across an oil lamp containing a magical genie. They quickly become friends, as the genie assists Aladdin in wooing the woman of his dreams – the Sultan’s daughter, who is expected to marry a Prince.

A lot of familiar Disney tropes can be drawn from this description, as well as the classic Hollywood stereotypes of Arabs mentioned previously.

In her response to the 2019 Aladdin, USC Professor Evelyn Alsutany points to older films such as The Sheik (1921) and Arabian Nights (1942) and notes their portrayal of the Middle East as “a monolithic fantasy land – a magical desert filled with genies, flying carpets and rich men living in opulent palaces with their haram girls” (3 2019, USC Dornsife). It is clear that Disney applied these tropes to their film.

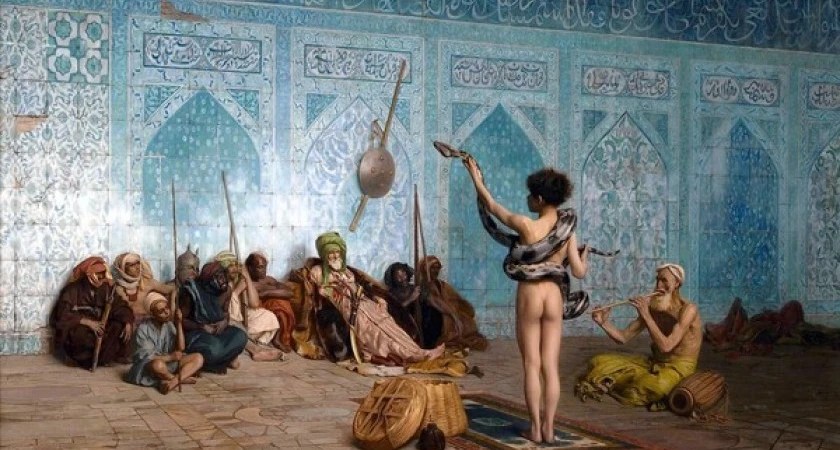

The Snake Charmer by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1879)

The depiction of Agrabah’s cultural scene brings The Snake Charmer to mind – a notable Orientalist oil painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme. The French artist’s representation of Middle-Eastern civilisation ignited debate after it became the face of Edward Said’s 1978 attack on orientalism. Said believed that this image helped perpetuate views of Middle Eastern people as “subservient”. Resemblance of this painting can easily be found in the original Aladdin, for the titular character brushes past multiple one-man shows, including a man who breathes fire, as well as a sword swallower. These are instances of what Labrusse refers to as “Hollywood Arabia” (1). The culture is presented as “barbaric”; a word also used to describe their way of living in the film’s opening song titled Arabian Night.

Another aspect of orientalism can be found in the character design choices. Outside of both Aladdin and Princess Jasmine (who each resemble your typical fresh-faced Disney leads), the screen is dominated by hooked noses, thick beards, and even thicker Middle Eastern accents. The skin tones are also noticeably darker than that of the two leads – who also happen to share American accents. Bullock and Zhou point out that “it is peripheral characters whose job it is to populate ‘Agrabah’ with Arab or Muslim-ish people” (2). They point to the apple seller in particular, who at one point threatens to cut off the Princess’ hand.

Wikipedia – Aladdin Disney Characters

The city is portrayed as backward. Aladdin and Jasmine – the two Westernised leads – spend the entirety of the film attempting to rebel against the nature of their culture – which is portrayed as overly traditional and violent. By telling a story from the perspective of a ‘street rat’, the film paints a dark picture of Arabian life, regardless of intention. Bullock and Zhou argue that Aladdin’s journey greatly resembles that of the ‘American dream’ – “like typically young and enterprising American upstarts or entrepreneurs, he used his ingenuity (along with a lot of luck) to escape such a label and to attain true love and happiness” (2) – thus painting a clear picture of a Westernised tale of the East. Jasmine’s need for independence plays similarly into American values – in this case, their vision of feminism.

By playing into tired stereotypes and telling a highly Westernised tale, it can be argued that Walt Disney Pictures – despite crafting an instant classic in the eyes of many – failed to produce an authentic portrayal of Saudi Arabia through Aladdin.

And it would appear that in spite of their efforts, the company would go on to repeat similar mistakes through their 2019 live-action remake, as it maintains much of the orientalism on display in the animated version.

Although there are some alterations, the main concept remains intact. The film, led by famed English director Guy Ritchie, once again portrays Jasmine’s struggle through a Western lens. The casting of Naomi Scott – a light-skinned, British Indian actress – as Princess Jasmine drew criticism not entirely dissimilar from the response to the design of her animated predecessor.

Naomi Scott as Jasmine (2019)

The choice to not to cast an actress of Middle Eastern descent also raised questions over the authenticity of the project, for another common criticism associated with the 1992 animated release concerns the depiction of Arabian culture as being interchangeable with other Eastern cultures. The casting of Scott sparked fear over this aspect being carried over. These fears would go on to be realised, as Alsultany observes “belly dancing and Bollywood dancing, turbans and keffiyehs”, along with Iranian and Arab accents which “all appear in the film interchangeably” (3).

Despite the removal of the more blatant stereotypes, Ritchie still manages to repeat many of the oriental aspects of the original – including the presence of American accents. Although these two films can easily be written off as ‘entertainment’ and nothing more, many still yearn for a nuanced portrayal of the Middle East – one free of Western influence – and it would appear that there are still ways to go yet.

Bibliography

(2) Bullock, K & Zhou, S. (2017) Entertainment or blackface? Decoding Orientalism in a post-9/11 era: Audience views on Aladdin, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, Vol. 39

(1) Labrusse, R. (2022) Deconstructing Orientalism, Manazir Journal, Vol.3

Aladdin, Rotten Tomatoes, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/disneys_aladdin

(3) Alsultany, E. (28 May, 2019) How the new Aladdin stacks up against a century of Hollywood stereotyping, USC Dornsife, https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/3020/aladdin-movie-and-hollywood-stereotyping/

Guy Ritchie, IMDb, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0005363/

Hibri, C. (13 Feb, 2023) Orientalism: Edward Said’s groundbreaking book explained, The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/orientalism-edward-saids-groundbreaking-book-explained-197429

Razzouk, D. (13 Sep, 2022) Why Are Kids Movies Obsessed with Orientalism? https://kazamind.com/kids-movies-and-orientalism/

Shatz, A. (20 May, 2019) ‘Orientalism,’ Then and Now https://www.nybooks.com/online/2019/05/20/orientalism-then-and-now/

Leave a comment